Monday, April 12, 2021

Cultural Contexts of COVID-19: Improving Pandemic Responses

Saturday, August 1, 2020

Friday, July 31, 2020

WHO project on cultural contexts of health and well-being adopted in U.S.

WHO/Europe is pleased to announce that the cultural contexts of health and well-being (CCH) project, which it pioneered and established, will now also be rolled out in the United States of America.

Vanderbilt University will lead the United States-based CCH programme. This initiative has been made possible by support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which has provided a 3-year grant totalling US$ 600 000.

“Our cultural beliefs shape the way we think about health,” said Karabi Acharya, Director of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. “We draw from the experiences of countries around the world that bring the relationship between culture and health into sharper focus. Leveraging that global learning, this project will explore culture’s impact on our overall health and well-being in the United States.”

Nils Fietje, Research Officer at WHO/Europe, added, “We are delighted to see that the work being done in the WHO European Region can be of use and inspiration elsewhere. It has become abundantly clear that health insights on matters such as culture are a critical component to finding solutions that are contextually integrated and thereby fit for purpose.”

Ted Fischer, Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Center of Latin American Studies, will lead the work. Fischer has served as an external advisor for WHO/Europe on topics of culture and health over the last 4 years.

“The medical field has been moving toward a model of considering the whole person, not just the disease, for a while now, and this project presents a great opportunity to rethink how we do medicine in ways we might not have considered before,” Fischer said. “And that’s really exciting.”

WHO project on cultural contexts of health and well-adopted in U.S.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Sunday, July 19, 2020

Creating Value Worlds with Third Wave Coffee

Wednesday, July 8, 2020

Cultures of Health and Sickness in the COVID Era - Le Monde Diplomatique

Cultures of health and sickness

A. David Napier and Edward F Fischer

- Le Monde diplomatique https://mondediplo.com/2020/07/04uganda

A group of researchers, led by David Mafigiri at Makerere University in Uganda, began collecting data this January for a long-planned health vulnerability assessment to identify what makes people and communities more vulnerable or resilient to infectious diseases. This study was in place well before the Covid-19 pandemic as part of Sonar-Global, a European Commission-funded research programme, and the team could amend questions based on current developments.

The data is now being analysed. But it is clear that, since lockdowns are still in place globally for fieldworkers and there is a hold on almost all face-to-face public health research, Uganda may have the only systematic real-time data on how people in at-risk communities conceptualise and respond to the virus.

The information the assessments collected is notable. The interviews lasted between one and three hours, much longer than a normal health survey. Instead of taking blood samples and asking multiple choice questions, researchers met participants in their homes and had structured but wide-ranging conversations about access to services, about availability of medical care and other health-related information, and about local conventions, practices and norms — ‘culture’.

Why culture? And why invest time and effort on things apparently unconnected with health and infectious disease? Because infectious viruses are about social networks and cultural norms, as much as about microbes. As science tells us, viruses are inert, unable to attack us. We transmit viral data though our social networks and cultural pathways. We give viral information to each other by how we live and what we do. Otherwise viruses just sit inert, sometimes for thousands of years. So understanding cultural contexts is just as important as sequencing genomes in tackling viral outbreaks.

Culture is nonetheless downgraded. Most of the time, when medical researchers try to work culture into their models, they fall back on tired stereotypes about local beliefs as obstacles to biomedical care, a supposed opposition of culture and science. In this paradigm, social scientists are lined up to help ‘real’ scientists determine why culture keeps others from doing what’s medically recommended.

A broader understanding of culture recognises its varied potential. Though clinicians may see culture as an obstacle to health, it is also a source of enduring trust. Moreover, it is not just something ‘they’ have: healthcare providers, scientists and policymakers all have their own cultures of practice, which inform their unique perspectives and encourage them to work together.

Cultures of practice However, the underlying and often taken-for-granted assumptions of culture about what is feasible can also limit innovative thinking. That’s why we use the word culture pejoratively to describe the intransigence of institutional cultures, political, academic or professional. In this sense, accounting for the cultural contexts of health and wellbeing is a primary health determinant — why ‘the systematic neglect of culture in health and healthcare is the single biggest barrier to the advancement of the highest standard of health worldwide’. That’s because culture is, in fact, the key to addressing health equity, especially when providers and target populations operate under different shared understandings about what matters most biologically and socially.

Thus, a cultural context of health approach is critical in responding to Covid-19. Because governments not previously concerned about health equity feel they must blame others for the impact of their own negligence. Because thinking of Covid-19 as only a medical challenge fuels xenophobic fears about outsiders. Because humanitarian action groups talk about working with communities even as inequalities within communities are exacerbated by the crisis. And because, given the socially sanctioned, chronic neglect of citizens already on the margins, Covid-19 pushes those on the edge into overt calamity coping. The taken-for-granted assumptions of cultures of practice give us a sense of belonging and trust, but sometimes blunt creative thinking and social innovation. For our assumptions help little in times of uncertainty. We know this because, when a disaster happens, so many show up late and with outdated equipment.

What can a cultural understanding of Covid-19 vulnerability tell us? We don’t need more research to recognise that the elderly, the homeless and unemployed single parents are especially at risk. They’re already vulnerable socially and economically, and, to our shame, become even more so when their fragile survival strategies are even more challenged.

But inequalities are always exaggerated in a crisis, and then many initially less vulnerable people are also pushed across capability and opportunity thresholds and into conditions of real peril.

That is why Uganda can now tell us more than we might expect. To understand what is happening in real time with real people, we need, as did David Mafigiri, to assess vulnerability before a disaster; like his own research team in Uganda, we need an extant interest in the disadvantaged. Ongoing empathy is critical. Without that, you have no access to what you should have known and now can’t. Your belated concern rings hollow in the face of that failure, which makes you liable to blame others. Indeed, organised humanitarian action all but stops in Covid-19, as we have little way of knowing what’s really happening on the ground among those most vulnerable, who live alone and without access to online services.

In response to such new instability, the World Health Organisation (WHO) rightly wants a ‘Just Recovery from Covid-19’. That, of course, is critical. But what we need equally is a just preparedness before an epidemic. We have to do the hard work of creating cultures of trust and solidarity in advance, and resist salvation narratives in which epic actions create save-the-world medical heroes and destructive villainous viruses.

In welfare states, where trust in government has remained relatively stable, there are few heroic stories, because stability and a commitment to the common weal lessened the need for bombast well before Covid-19 incited it. Initiatives such as Cities Changing Diabetes (a Danish community engagement strategy sponsored by Novo Nordisk) demonstrate how prior work around understanding health vulnerabilities translates, despite its focus on a non-communicable disease, into actionable understanding in the crisis. That is because the programme has been assessing global health vulnerabilities since 2015, years before Covid-19.

New vulnerabilities Vulnerability emerges variably, at different times and places. This means that, while already vulnerable populations become even more so under stress, new vulnerabilities emerge that often outstrip old ones. Service industry employees without health benefits and dependent on daily income become more vulnerable, especially where they now have to go back to work, than those elderly who can stay at home and wait it out. High-income physicians without adequate protective gear are as vulnerable as those with chronic pre-existing conditions. Places we previously thought of as havens are anything but: in Europe and the US, the most vulnerable are in ‘care’ institutions: nursing homes, shared housing, prisons.

We failed these vulnerable groups because their illness experiences are socially driven, and that is too often separated from health. We look instead for specific risk factors in isolation without seeing how compounding, already-existing, stressors push populations into extreme vulnerability during a crisis — especially those with few choices and nowhere to go. In the UK, ethnic minorities are dying at higher rates from the virus than the rest of the population; and in the US, African Americans have far higher mortality rates than white and Asian American populations. Yet, as crises widen existing rifts in societies, they also open up opportunities for communities to come together in ways unthinkable in normal times; in Rio de Janeiro, for instance, gangs in several favelas imposed shelter-in-place orders to reduce transmissions.

Communities must often adapt on their own, because political systems are vulnerable to pandemics too: the global crisis is making clearer what is important at national and local levels, and what is less so. It shows us what we collectively value, and makes us reconsider often-tacit assumptions. Indeed, our judgments of what is essential have also changed across the globe, providing a singular opportunity for institutions and governments to rebalance private gain and public good.

This adjustment can go either way. On the one hand, speaking of the virus as a foreign enemy incites xenophobia, with the social category of ‘insider’ — the ‘we’ in ‘we are all in this together’ — getting smaller and smaller. On the other, the pandemic has catalysed new alliances, as with Black Lives Matter and anti-police protests. Mistrust in the institutions of government may be the only thing uniting the far right and far left in countries like the US and Brazil.

That is why ‘just preparedness’ matters, and also why Uganda might lead the way in understanding the human impact of Covid-19. Because this pandemic is not just about an infectious threat, but about the urgency of caring beforehand, and about the steep decline in social trust that emerges quickly in unequal settings where global neoliberal economics have undermined public wellbeing.

Fortunately, that decline has created opportunities in surprising places. Gangs in favelas may seem a stretch when policymakers think about health systems change, but some far-sighted private companies have been quicker than many governments to recognise and respond to shifting public sentiment: sending their employees to work from home, speaking out against racism and calling for more government guidance. However, not all businesses are equal: companies less vulnerable to shareholder pressure to maximise short-term profits are better able to consider their potential long-term future roles, and not just in the next quarter — recognising that an economy cannot survive unless nation states and their citizens have stability, enough income, and access to robust and well-funded care.

Mistrust in business There have been calls by world leaders, including Ursula von der Leyen, head of the European Commission, for a new Marshall Plan to improve abysmal levels of trust in business recorded by Richard Edelman’s Trust Barometer. But that mistrust can only be reversed by sustained long-term commitments that are faithful to a range of stakeholders — including employees, clients and the social and natural environments we all depend upon for survival.

Divisive political leaders, like Donald Trump or Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, may blame the left, or the Chinese, or the CIA for Covid-19, based on alternative, often paranoid political narratives that divide local communities. That is because for opportunists, big or small, the crisis remains an intractable intrusion into populist narrative worlds built on political delusion. But the virus’s deadly materiality resists rhetorical defences and counter-factual denials, even if some seem intent on taking the ship down, or watching it sink while drowning in denial. The states lacking welfare can only blame others.

Social trust and faith in institutions are therefore crucial for the collective actions required to halt viral transmission. We have to coordinate our social behaviours in uncomfortable, inconvenient, and even personally painful ways. They are vital to collective wellbeing and require sacrifice; a sense of commonality and social solidarity must be based around shared values — culture. A crisis in governance, correlates with, and can be directly mapped onto, a crisis in trust, because where we find trust is key.

As the US pulls support from the WHO, there is a serious question: where do we go for an independent and trustworthy adjudication on health risk? The world’s biggest healthcare charity, the Gates Foundation, has always espoused magic bullet answers to health problems and is uninterested in the complex social drivers of our wellbeing. The Centers for Disease Control is a US federal agency that works well in good times but in bad times is vulnerable to partisan political nonsense. Without socially trustworthy institutions, how are we to respond to growing uncertainty?

Sustained uncertainty And how, finally, can we learn to deal with sustained uncertainty and the psychological vulnerability it causes? If many governments cannot lead equitably, and viruses are just information we share, there must be other drivers of Covid-19 we can act on. Other factors remain under-represented: the more people there are on the planet, the more often viruses like Covid-19, which are more contagious but less lethal than Ebola, will connect us. And that is a big problem, not only because science, in the absence of a vaccine, still medicalises a pandemic almost entirely driven by our social responses, but because there are more of us to circulate and adapt to that viral information.

This really matters with Covid-19, since, if lasting immunity doesn’t happen soon, we need to rethink the social contract in ways that run counter to those who advocate for biodeterminism or xenophobic scapegoating or maximising self-interest. Otherwise, when the pandemic abates even temporarily, we risk going back to ‘normal’, forgetting what we might have learned until the next infectious disease outbreak, when we will again be completely surprised by what we should have expected. We need to consider the needy before that happens — to put heart and soul into thinking about both how we live together with uncomfortable uncertainty, and how we address together the social and cultural drivers of health vulnerability.

A David Napier is professor of medical anthropology at University College London, innovations lead for Sonar-Global, global academic lead for Cities Changing Diabetes and international chair of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation committee on the Cultural Contexts of Health and Wellbeing initiative. Edward F Fischer is professor of anthropology and health policy at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he also directs the Center for Latin American Studies and the Cultural Contexts of Health and Wellbeing initiative.

Copyright ©2020 Le Monde diplomatique — distributed by Agence Global

—————-

Released: 07 July 2020

Word Count: 2,139

—————-

Friday, May 1, 2020

Monday, November 12, 2018

‘Now is the Time of Monsters’: The Painful Birth of a New World Order

Thursday, November 8, 2018

Tuesday, November 6, 2018

Thursday, November 1, 2018

Friday, March 30, 2018

Thursday, December 28, 2017

Economy, Happiness, and the Good Life: An Interview with Edward F. Fischer

|

| GB. England. New Brighton. From ‘The Last Resort,’ 1983-85, Martin Parr. |

KR: What do you understand by the notion ‘the good life’?

Edward F Fischer: I see you are starting off with the trick questions. A large part of the attraction of the phrase is precisely its semantic slipperiness and strategic ambiguity. We may all agree . . . continue at http://kingsreview.co.uk/articles/economy-happiness-good-life-interview-edward-f-fischer/

Tuesday, October 18, 2016

Eating Identity: Nourishment and the Cultural Contexts of Food

We eat for nourishment, but food is about much more than nutrition. What we eat is meaningful, and food is an especially intimate area of daily life, tightly linked to our conceptions of self. Think about your own food preferences: a nostalgic meal from your childhood, a treat you indulge yourself with on special occasions, a religious sanction against certain foods. In these ways, food is not only at the heart of our material subsistence, it is at the core of our identity as well, deeply associated with family, hearth, home, and community. We are what we eat, conceptually as well as biologically.

Understanding this becomes especially important when we look at nutrition from a public health perspective. In a situation that would have been unimaginable for most of human history, over-nutrition has become one of the biggest problems for health and chronic diseases in many parts of Europe and the U.S., eclipsing smoking as public health enemy #1. The chronic and non-communicable diseases that are the big burden these days (heart disease, cancer, diabetes, stroke) are often connected to diet.

The WHO’s Health 2020 report advocates people-centered approaches to public health, looking at both the whole person and the whole society. This is especially relevant for nutrition because it is so connected to different aspects of life, from our cultural and idiosyncratic preferences to state subsidies and agricultural policy.

Poor nutrition is not just an over-abundance of macro-nutrients or a deficiency of micro-nutrients: it is based on cultural traditions and personal histories; the natural environment and geographies of inclusion and exclusion; about large food corporations and grocery store marketing as well public policy and regulations. This is to say that both structural conditions and cultural practices affect nutritional choices.

Thinking of food and identity, what comes to mind first might be kosher or halal cuisines, or perhaps vegetarian or vegan preferences. These are certainly important aspects of religious and social identity, but the link works at a much more mundane levels as well. Our quotidian food choices reflect our preferences and values, and identity: eating organic (or not), eating fast food (or not), liking broccoli (or not), and so on.

Since food is so integral to identity, it is tricky to tinker with. And food choices not only reflect identity, but identities can become literally embodied through eating. For example, many Maya people in Guatemala claim not feel full unless they eat corn tortillas (often a dozen or more with every meal); I have heard Germans claim the same feeling and physical craving for black bread.

Eating is also usually a group activity, and as such a primary site for socialization, family binding, and group identity reinforcement. Yet nutritional recommendations often focus just on the individual. And since individual choices affect others, change cannot happen with just the individual, it would involve the whole family.

And just as eating is a group activity, also provisioning is often an expression of love and caring. Anthropologist Daniel Miller has show how food treats are especially important in this regard: choosing for significant others what they might want. Miller shows that grocery shopping, far from the hedonistic indulgence that the term “consumerism” invokes, is more about provisioning for one’s family, expressing one’s concerns for loved ones.

Packaged and processed foods are a big contributor to poor nutrition, and so are deservedly the target of ire among nutritionists and public health advocates. A number of efforts to impose a “soda tax” have been tried around the world; in Mexico it has had a dramatic and measurably impact in just a few years. All the same, we should also recognize that such foods are one of the few affordable luxuries for poor families, a way to demonstrate their love for their children when they cannot give them much else. It is well and good to try to curb snack food consumption, but keep in mind that it may be more than a snack that has to be changed.

Finally, when we talk about the health impacts of nutrition, we often reduce eating down to certain numbers. My colleague Emily Yates-Doerr, in her book the Weight of Obesity, calls this the metrification of diets: the number of calories and grams of fat, the percentages of daily allowances for vitamins and minerals. This metrification reduces the richness of eating and the sociality around it to these metrics of macro- and micro-nutrients. Many of us have become accustomed to this way of thinking about food, reading labels on the fly in the supermarket. Food and eating is about love and identity as much as calories, but how do we translate “love” into grams or ounces?

Just because something is supposed to be “good for you” is often not enough to change behavior. Diet and food choices need to be looked at holistically, as part of broader lifeways and family and social networks. Labeling regimes can inform consumer decisions and move the market, and soda taxes and other nudges can make a difference, but ultimately public health programs working on nutrition need to engage people through their customs and beliefs rather than work at odds with them.

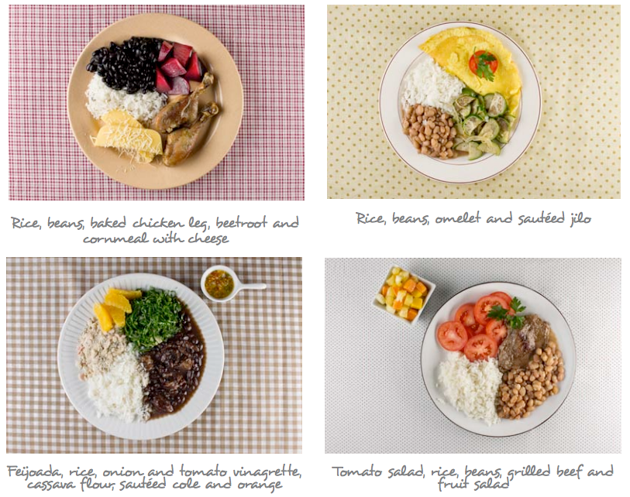

In an innovative approach, Brazil has adopted what they call “food-based” dietary guidelines that seek to build on cultural norms and preferences rather than fight them. Rather than giving percentages recommended for different foodstuffs (as with the traditional food pyramid), Brazil adopted 10 broad principles and illustrate them in public service ads in terms of a plate prepared for a typical meal.

- Make natural or minimally processed foods the basis of your diet

- Use oils, fats, salt, and sugar in small amounts

- Limit consumption of processed foods

- Avoid consumption of ultra-processed foods

- Eat regularly, deliberately, and with others

- Shop in places that offer a variety of natural or minimally processed foods

- Develop, exercise and share cooking skills

- Plan your time to make food and eating important in your life

- Out of home, prefer places that serve freshly made meals

- Be wary of food advertising and marketing

Sunday, August 21, 2016

Third Wave Coffee and the Formation of Taste (and Value)

In 2015 the SCAA unveiled a new flavor chart for specialty

coffee. Working with researchers at UC Davis and Kansas State, the Coffee

Taster’s Flavor Wheel offers a lexicon of coffee terms coming from “the

frontiers of sensory science methods and analyses.” They described the process

using technical language (“an Agglomerative Hierarchical Cluster (AHC) analysis

was performed on the results from the sorting exercise to group the flavor

attributes into different categories (or clusters) represented visually by a

dendrogram”) (Sage 2016).

In 2015 the SCAA unveiled a new flavor chart for specialty

coffee. Working with researchers at UC Davis and Kansas State, the Coffee

Taster’s Flavor Wheel offers a lexicon of coffee terms coming from “the

frontiers of sensory science methods and analyses.” They described the process

using technical language (“an Agglomerative Hierarchical Cluster (AHC) analysis

was performed on the results from the sorting exercise to group the flavor

attributes into different categories (or clusters) represented visually by a

dendrogram”) (Sage 2016).Saturday, August 20, 2016

Broccoli, Anthropology, and the Humanities

Broccoli, Anthropology, and the Humanities: Caitlin Patton discusses how the work of Ted Fischer, an anthropologist focused on food culture, specifically the cultivation of broccoli in Guatemala, inspired her choice to study at Vanderbilt University.

Monday, August 1, 2016

Imagining the Future & Economic Fictions

Friday, November 13, 2015

Q&A: Ted Fischer of Vanderbilt | Nashville Post

Ted Fischer is professor of anthropology and director of the Center for Latin American Studies at Vanderbilt University. Over a five-year period, he teamed with Steve Moore (head of Middle Tennessee-based Shalom Foundation) and multiple VU students on a malnutrition-oriented and social enterprise effort called NutriPlus, which produces the supplement, Mani+.

The supplement (a fortified nut paste that provides calories, protein, fat, vitamins and minerals essential to brain development in babies and toddlers) is used to specifically address the nutritional deficiencies seen in Central American children. It is the first ready-to-use supplementary Food (RUSF) to be both locally produced and locally sourced in Guatemala City, Guatemala, creating local jobs and supporting local farmers.

The new facility (read more here) opened on Sept. 23 and will eventually mass produce Mani+. Eventually, Fischer and Moore hope to produce 25 tons of Mani+ a month, reaching about 25,000 children.

Post Managing Editor William Williams recently chatted with Fischer regarding the effort.http://nashvillepost.com/blogs/postbusiness/2015/10/19/qa_ted_fischer_of_vanderbilt

Thursday, October 1, 2015

Friday, September 4, 2015

Health, Culture, and Wellbeing: Beyond Seeing Culture as Obstacle

While there is a growing understanding that “culture” plays a crucial role in health and development, the concept as it is invoked generally relies on very traditional definitions. Common definitions of culture in public health understand it to be “shared values, beliefs, and practices.” Note that here “culture” is used as a noun, denoting bounded groups defined by lists of traits.

But we should see cultural forms as opportunities, not as obstacles, to health

A human-centered approach to health and wellbeing, should adopt contemporary understandings of culture as dynamic, future oriented, and driven by agency. We in anthropology now see culture as much more of a fluid process, a process rather than a thing. Cultural actors are always improvising, actively creating meaning out of the resources at hand.

We have also traditionally put too much emphasis on the historical determinants of culture and adherence to tradition. My view is that we should think of cultural orientations not just as not endowments but as future-oriented desires. Arjun Appadurai defines culture as “a dialogue between aspiration and sedimented traditions.”

In this view, culture opens the door for new opportunities for engaging communities and understandings of well-being.

The full report in English and Russian is at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/data-and-evidence/cultural-contexts-of-health/beyond-bias-exploring-the-cultural-contexts-of-health-and-well-being-measurement

Wednesday, July 1, 2015

Voting for Our Better Selves; and Rules to Flourish By

Indeed. As I argue in The Good Life: Aspiration, Dignity, and the Anthropology of Wellbeing, we aspire to be certain sorts of people -- a key part of our identity is not just who we are, but who we want to be. Our aspirations reflect certain sorts of values, what matters most to us in the big scheme of things. These aspirations, and our better selves, can be undermined by short-term gains and hedonic pleasures. And so we need leaders to remind us of our better selves and guide us down the often more arduous path of long-term personal and collective fulfillment.

For these same reasons, we also need rules to hep us be our better selves. A recent RadioLab episode (Nazi Summer Camp) looked at how the U.S. treated the 500,000 or so German and Japanese POWs in U.S. camps. It turns out we treated them exceedingly well, fully following the letter and spirit of the Geneva Convention, even when we saw that the Japanese and Germans were not so scrupulous in their adherence. Significantly, we treated the U.S. citizens of Japanese descent much worse at the internment camps. As U.S. citizens, paradoxically, there were no international rules to govern their treatment, and the country showed it worse side. Similar examples of how rules can help us be the sort of people we say we want to be can be found in Lynn Stout's excellent book Cultivating Conscience and in my book The Good Life.