We eat for nourishment, but food is about much more than nutrition. What we eat is meaningful, and food is an especially intimate area of daily life, tightly linked to our conceptions of self. Think about your own food preferences: a nostalgic meal from your childhood, a treat you indulge yourself with on special occasions, a religious sanction against certain foods. In these ways, food is not only at the heart of our material subsistence, it is at the core of our identity as well, deeply associated with family, hearth, home, and community. We are what we eat, conceptually as well as biologically.

Understanding this becomes especially important when we look at nutrition from a public health perspective. In a situation that would have been unimaginable for most of human history, over-nutrition has become one of the biggest problems for health and chronic diseases in many parts of Europe and the U.S., eclipsing smoking as public health enemy #1. The chronic and non-communicable diseases that are the big burden these days (heart disease, cancer, diabetes, stroke) are often connected to diet.

The WHO’s Health 2020 report advocates people-centered approaches to public health, looking at both the whole person and the whole society. This is especially relevant for nutrition because it is so connected to different aspects of life, from our cultural and idiosyncratic preferences to state subsidies and agricultural policy.

Poor nutrition is not just an over-abundance of macro-nutrients or a deficiency of micro-nutrients: it is based on cultural traditions and personal histories; the natural environment and geographies of inclusion and exclusion; about large food corporations and grocery store marketing as well public policy and regulations. This is to say that both structural conditions and cultural practices affect nutritional choices.

Thinking of food and identity, what comes to mind first might be kosher or halal cuisines, or perhaps vegetarian or vegan preferences. These are certainly important aspects of religious and social identity, but the link works at a much more mundane levels as well. Our quotidian food choices reflect our preferences and values, and identity: eating organic (or not), eating fast food (or not), liking broccoli (or not), and so on.

Since food is so integral to identity, it is tricky to tinker with. And food choices not only reflect identity, but identities can become literally embodied through eating. For example, many Maya people in Guatemala claim not feel full unless they eat corn tortillas (often a dozen or more with every meal); I have heard Germans claim the same feeling and physical craving for black bread.

Eating is also usually a group activity, and as such a primary site for socialization, family binding, and group identity reinforcement. Yet nutritional recommendations often focus just on the individual. And since individual choices affect others, change cannot happen with just the individual, it would involve the whole family.

And just as eating is a group activity, also provisioning is often an expression of love and caring. Anthropologist Daniel Miller has show how food treats are especially important in this regard: choosing for significant others what they might want. Miller shows that grocery shopping, far from the hedonistic indulgence that the term “consumerism” invokes, is more about provisioning for one’s family, expressing one’s concerns for loved ones.

Packaged and processed foods are a big contributor to poor nutrition, and so are deservedly the target of ire among nutritionists and public health advocates. A number of efforts to impose a “soda tax” have been tried around the world; in Mexico it has had a dramatic and measurably impact in just a few years. All the same, we should also recognize that such foods are one of the few affordable luxuries for poor families, a way to demonstrate their love for their children when they cannot give them much else. It is well and good to try to curb snack food consumption, but keep in mind that it may be more than a snack that has to be changed.

Finally, when we talk about the health impacts of nutrition, we often reduce eating down to certain numbers. My colleague Emily Yates-Doerr, in her book the Weight of Obesity, calls this the metrification of diets: the number of calories and grams of fat, the percentages of daily allowances for vitamins and minerals. This metrification reduces the richness of eating and the sociality around it to these metrics of macro- and micro-nutrients. Many of us have become accustomed to this way of thinking about food, reading labels on the fly in the supermarket. Food and eating is about love and identity as much as calories, but how do we translate “love” into grams or ounces?

Just because something is supposed to be “good for you” is often not enough to change behavior. Diet and food choices need to be looked at holistically, as part of broader lifeways and family and social networks. Labeling regimes can inform consumer decisions and move the market, and soda taxes and other nudges can make a difference, but ultimately public health programs working on nutrition need to engage people through their customs and beliefs rather than work at odds with them.

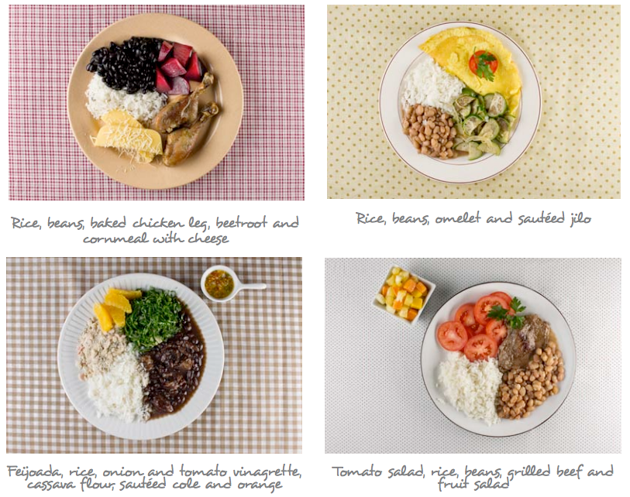

In an innovative approach, Brazil has adopted what they call “food-based” dietary guidelines that seek to build on cultural norms and preferences rather than fight them. Rather than giving percentages recommended for different foodstuffs (as with the traditional food pyramid), Brazil adopted 10 broad principles and illustrate them in public service ads in terms of a plate prepared for a typical meal.

- Make natural or minimally processed foods the basis of your diet

- Use oils, fats, salt, and sugar in small amounts

- Limit consumption of processed foods

- Avoid consumption of ultra-processed foods

- Eat regularly, deliberately, and with others

- Shop in places that offer a variety of natural or minimally processed foods

- Develop, exercise and share cooking skills

- Plan your time to make food and eating important in your life

- Out of home, prefer places that serve freshly made meals

- Be wary of food advertising and marketing